Garry Cobb

The last time the world demonstrated such a lack of humanity toward migrants was in 1939. Archie Dickson shone a light in that darkness.

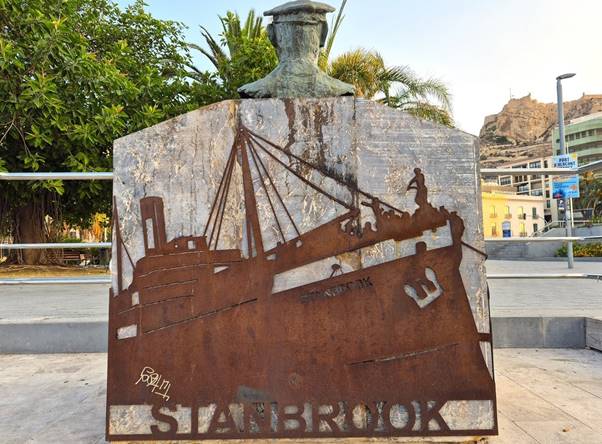

I pass him on my morning jog. The raucous crowds still pouring out of the Alicante City nightclubs onto the marina at sunrise on a Sunday morning. They don’t see him. They hardly see the crumpled plastic bottles they leave in their wake, still buzzing from dancing the night away on Tequila shots. If there was a flat space around him, he’d be holding their empty glasses. But Archie’s eyes can’t see. Neither will he remember any youthful exuberance growing up in Wales with twelve siblings. He joined the Merchant Navy at 15. Now he faces the other direction, which is where, in 1939, he watched the ragged crowds flooding towards him begging for help. He is, after all, just a memorial bust sitting on the quayside, frozen at the age of 47 when he died.

I leave a flower to the crew of the SS Stanbrook and their captain, father of two, Archibald Dickson and quietly say, ‘thank you, Archie.’

The SS Stanbrook saw Spain in 1939, polarised and divided. Tearing itself apart by civil war. On the one side was Franco’s Falange and right-wing Nationalists. Mostly landowners, businessmen, socially conservative Roman Catholics and members of the military. On the other side were the Republicans: Workers, mostly agricultural labourers and an educated middle class including many writers, poets and artists like Pablo Picasso who painted his anti-war ‘Guernica’ in 1937. With chronic shortages, some lice-ridden soldiers were fighting in bare feet. After serious injuries they might find themselves in a hospital with just one syringe and discharged practically naked due to a shortage of clothes.

The port at Alicante had been blockaded not only by the encroaching Spanish Nationalists, but by Hitler’s Nazi war planes and some of Mussolini’s 80,000 Italian troops. By dodging one of Franco’s destroyers in bad weather, the British merchant cargo ship SS Stanbrook, a 230-foot-long tramp steamer, made it into Alicante port on the 19 March 1939 with orders from the ship’s owner to load only oranges, tobacco and saffron and get out. What Archie saw on arrival was a far cry from tourists sipping Cava or skinny lattes at the beachfront tapas bars today. He was met by thousands of hungry Republican refugees in ragged clothes clutching their few possessions on the quay of Alicante City. Amongst them were soldiers of the Republican army, International Brigade members, academics, artists, trade unionists, politicians, foreign advisers, and women and children of all ages. They were fleeing the Nationalists and waiting for ships to take them to safety. But they waited in vain. The Stanbrook was one of the last ships to leave Alicante harbour before it fell to the fascists. Alicante City was in chaos. The fascists were blockading and conquering the city as the elected democratic Republican government fell.

The cities of Murcia and Valencia had already fallen into the hands of the Falange on 8 March 1939. Thousands headed to the port city of Alicante, still held by the Republicans, to try to escape into exile on the last few ships to leave.

In total, somewhere between 10,000 and 12,000 Spanish Republicans fled to Africa. They were arriving on the French Algerian coastline in anything that would carry them. Coastguard vessels, ships, sailboats or small boats. But they were going to be made to feel as welcome as a one-way ticket to Rwanda.

The Republicans were in no position to organise evacuations. As the conflict neared a gruesome end, about 500,000 had already died and things were going badly for the army of their democratically elected government. Their navy of about 4,000 men had already fled. Almost three years earlier, in August 1936, France joined Britain, the Soviet Union, Germany and Italy in signing a non-intervention agreement that would be ignored by the Germans, Italians and Soviets. Many civilians decided not to turn their backs on Spain. About 40,000 foreigners fought on the Republican side in the International Brigades, largely under the command of the Communists, with another 20,000 serving in medical or auxiliary units. ‘Aid Spain’ groups were set up across Britain to get supplies to the Republicans. But before the civil war was over, Britain and France threw in their hat with the Falange fascists and recognised Franco as victor and leader of Spain on 27 February 1939. It contributed to the fascists winning the war after Franco’s Falange went on to capture Madrid on 28 March which led to the surrender of the Republican government the very next day.

The world was in a febrile state. The second world war was only months away. In May 1939, with tens of thousands of supporters, Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts, the British Union of Fascists (BUF), were marching through London giving their Nazi salutes. Under the headline ‘Hurrah for the Blackshirts!’, the Daily Mail showed its true colours. Then, as now, I’m sure readers will tell you they ‘just buy it for the crossword.’

Two of the world’s worst despots at the time got together for a deal. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact saw Germany under Hitler and the Soviet Union under Stalin work on a secret protocol to partition Poland and divide Eastern Europe into German and Soviet ‘spheres of influence.’ Law-breaking authoritarians and criminals were taking a wrecking ball to world order. Sound familiar…?

In a letter to the Sunday Dispatch, published on 4 April 1939, Archie explained what he saw in Alicante City: “Among the refugees were all classes of people, some of them appearing very poor indeed and looking half starved and ill clad and attired in a variety of clothes ranging from boiler suits to old and ragged pieces of uniform and even blankets and other odd pieces of clothing.”

“Owing to the large number of refugees, I was in a quandary as to my own position, as my instructions were not to take refugees unless they were in real need. However, after seeing the condition of the refugees, I decided from a humanitarian point of view to take them aboard as I anticipated that they would soon be landed at Oran.”

Archie claimed that only some of his cargo had arrived and that the port authorities asked if he could ship 1,000 refugees to Algeria, so he started loading the refugees instead. The port authorities soon lost control of the “stampede”- in Archie’s words – clamouring to board the Stanbrook. The gangway “became choked with a struggling mass of people,” including guards and customs men abandoning their weapons to climb onboard.

On 28 March 1939, late in the evening, the Stanbrook slipped away with an estimated 2,638 passengers huddled together onboard.

As a little girl of 4-years old, Helia González remembered that cold night. “We arrived at the port by train from Elche; once there, a very long line separated us from a ship that seemed enormous to me, with a strange name and a lot of people. We, like everyone else, were afraid we wouldn’t be able to reach the gangplank that would allow us to get on board.” Helia’s father was a marked man. A union leader and founder of the Young Republican Left Party in her hometown of Elche. She added: “Finally, we reached the ship. Strong arms lifted me up. I saw a smiling face, a sailor’s cap, and he kissed me on the cheek. He didn’t say a single word, but that hug, that look, promised something good… it was him, it was Dickson, and there was no more danger. It rained that night. Mother shared an omelette with a family from Malaga, a couple and a boy my age, made with one egg and two potatoes and a little fat.” Archie wrote: “I was able to provide the weakest refugees with some coffee and some food. The vast majority had enough bread to last them all the way to Oran; the night was clear but cold, and I think the suffering of these people standing on the deck all night must have been very bad.”

“We had only just got clear of the port when the air raid rumour or bombardment proved to be true and within 10 minutes of leaving the port a most terrific bombardment of the town and port was made and the flash of the explosions could be seen quite clearly from onboard my vessel and the shock of the exploding shells could almost be felt.”

A German bomb was dropped where the SS Stanbrook had been moored.

The vessel reached Oran in French Algeria some 20 hours later. But packed together on that cold night, their ordeal was not over. The port authorities wouldn’t allow the ship to dock. After some wrangling – including threatening to ram the ship into Oran’s harbour – Archie got his way. Then, under French rules, the port authorities impounded the Stanbrook and refused to let the refugees disembark.

Archie persuaded the authorities to at least let the women and children off. Their destination would be a men’s prison where they suffered the indignity of being stripped naked and washed and disinfected in front of the guards.

After three weeks, the Manchester Guardian reported: “Still 1,000 men on the ship who since they left Spain have had no opportunity to wash or change their clothes and have hardly enough space to lie down. They are never allowed on the deck for exercise… their food consists of half a loaf of bread a day and either tinned sardines or tinned paste.” According to Archie, their appearance was “pathetic, especially since they haven’t had a chance to wash or shave. Some of them have stripped off their clothes.”

The French authorities were openly hostile to the Spanish refugees. Yet, alarmed by the health hazards posed by housing over 1,000 refugees onboard an old tramp steamer, they finally gave up and interned the starving men along with the women in cold, lice-ridden concentration camps. Food was delivered to them by the Quakers, but still, many died.

At first, Franco demanded the Republican refugees be returned to Spain, but after some negotiations the French saw an opportunity to use most of the refugees of the Stanbrook as forced labour to build the Trans-Saharan Railway.

The French authorities initially demanded 205,000 French francs for the Stanbrook’s release from Juan Negrin’s Republican Government-in-exile, then raised the amount to 250,000 before finally settling for 170,000.

There were limited choices for Republicans fleeing for their lives. Most of the refugees arriving in Algeria were sent to Camp Morand near Boghari in the Sahara. The facilities at the camp were so wretched that its closure was recommended at the International Conference for Assistance to Spanish Refugees held in Paris in 1939. Nevertheless, it remained open.

Living in tents in the guarded camps would have been unbearable in the searing heat of the Algerian summer. And freezing in winter. Some tried to make an income to supplement the food shortages, making household items and selling them secretly. Some tried to escape and paid with their lives. Eventually, the refugees were released to integrate, to work or set up businesses. Most took up the opportunity to flee to other European countries or Argentina, Mexico or Cuba after the colonies gained their independence.

In France itself, hundreds of refugees escaping across the Spanish border into France were interned in squalid camps scattered across 15 improvised sites. They were often just barbed-wire enclosures without sanitation, some erected on deserted beaches. In the first six months almost 15,000 refugees died of malnutrition or dysentery in these ‘reception centres.’ The Vichy government moved many refugees to Nazi-controlled concentration camps. Almost 5,000 Spanish civil war veterans were to meet their death in the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

Once the French had emptied the internment camps of Spaniards after the Second World War, they filled them again with more foreign refugees from its war to keep its colonial hands on Algeria. After the eight-year war of independence in 1962, around 90,000 Harkis, mostly uneducated Muslims who had fought with the French, tried to seek asylum in France. Despite their persecution in Algeria for fighting against independence, they were refused the right to become citizens. Rather than exciting anti-immigrant feeling with an influx of poor Muslims, many were eventually turfed out of the concentration camps and rehoused in remote forest villages away from cities. Not until 2012, by way of an apology (and to pocket their vote), did President Nicolas Sarkozy publicly recognise France’s ‘historical responsibility’ in abandoning and interning the Harkis. Emanuel Macron followed suit in 2021.

During the Franco years, many Spaniards emigrated to Europe for work opportunities in the low paid service sector. In Britain we remember their contribution best in the shape of the hapless Manuel in the 70s TV comedy series, Fawlty Towers . Oh, how we laughed.

It was the acerbic American writer, Gore Vidal who wrote: ‘A good deed never goes unpunished.’ And there could have been no more horrible a demonstration of this when, only a few months after landing his shipload of refugees in French Algeria, sailing the SS Stanbrook from Antwerp to England on 19 November 1939, a German U-57 torpedo struck the port side. The ship sank, and the crew of 20, including poor Archie, were lost.

Once news of the death of Archie and the Stranbrook crew reached the inmates of the Boghari concentration camp in Algeria, they stopped what they were doing, bowed their heads, and observed a minute’s silence.

Part 2: Miguel and the victims left behind.

Those 15,000-or-so Republicans who failed to get away on any of the few ships that had left Alicante received little mercy from the victorious Italian fascist forces who successfully took the city on 31 March 1939. In desperate scenes, the Italian troops attacked, tortured and murdered the remaining victims gathered on the quay. Some Republicans chose to take their own lives.

The next day, on 1 April 1939, Franco announced the end of the civil war.

Picture: Archivo Municipal de Alicante

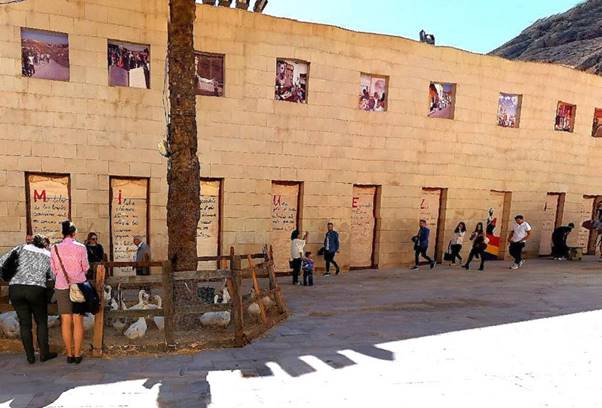

Many Republicans were rounded up and marched between a double line of soldiers pointing rifles and machine guns to a makeshift concentration camp at La Goteta, now a tram stop, and then to the notorious Campo de Los Almendros (Field of Almond Trees) concentration camp before being transferred to other camps for ‘ideological cleansing.’ The 200 x 80 metre plot was built and guarded by Italian troops. Just an open field. No shelter, little water and no food apart from what guards offered through the barbed-wire fencing.

Before arriving, some columns of Republican prisoners were machine-gunned from the nearby slopes of Santa Barbara Castle which caused panic and deaths. Many others went on to die of disease, suicide, forced labour or starvation. The almond trees were quickly stripped of the few remaining fruits from the previous year, and then of the leaves and tender new shoots for food. The trees were soon bare. Up to 2,000 died in the camp.

The Field of Almond Trees site is close to where the Plaza Mar 2 shopping centre stands today where shoppers wheel their supermarket trolleys round Carrefour, try on new suits in Massimo Dutti or pick Breezy Blue Eyeshadow from Yves Rocher. The memorial stands in the shade of an Almond tree remembering those poor, desperate men. The inscription on the memorial reads: “At dawn on 15 November 1939, the military forces which rebelled against the Second Republic shot these defenders of liberty and buried them in this common grave.” Alongside is a poem by Miguel Hernández entitled ‘El Tren de Los Heridos.’ (Train of the Wounded), which includes the poignant words: –

“Silence shipwrecked in the silence

of the mouths closed at night.

It does not cease to be silent or to traverse it.

It speaks the drowned language of the dead.

Silence.”

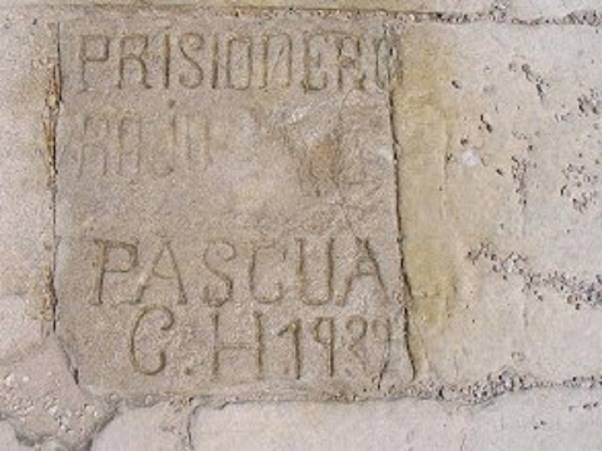

Others who fought the Nationalists and those caught waiting for ships in Alicante to take them to safety were punished severely. They were sent to several locations, including the city’s bullring or Santa Barbara Castlewhere some 4,000 victims were interned. Some left their names etched into the fortress floors where they are still visible today.

In his book, The Spanish Holocaust, Paul Preston writes: “Families were violently separated and those who protested were beaten or shot. The women and children were transferred to Alicante, where they were kept for a month packed into a cinema with little food and without facilities for washing or changing their babies. The men – including boys from the age of twelve – were either taken to the bullring in Alicante or to a large field outside the town, the Campo de Los Almendros, so called because it was an orchard of almond trees.”

The poet, Miguel Hernández was just one of many who missed boarding the Stanbrook. Just like fellow poet Federico García Lorca who was executed by a firing squad, Miguel also deplored fascism. He grew up poor in nearby Orihuela and lived with a father who chastised him for spending time with books rather than working as a farmhand. As soon as he finished his primary education Miguel was put to work. While he had been at school, he became friends with Ramón Sijé, a well-educated boy who had lent and recommended books to him. Ramón’s death would inspire Miguel’s most famous poem, ‘Elegy.’

Miguel Hernández was accused of being a communist commissar and of writing poems harmful to the Francoist cause, so he escaped to Portugal, another country led by a right-wing dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar. Miguel was arrested and sent back to Spain. Once there he was sentenced to death. Thankfully, with the help of some well-connected friends he was released from prison. But after heading home to Orihuela he was arrested again. This time he was sentenced to 30-years in prison. But he would never get out alive. Miguel was incarcerated in multiple jails under horrendously harsh conditions. He suffered pneumonia in Palencia prison, bronchitis in Ocaña prison and typhus and tuberculosis in Alicante City’s prison.

Miguel Hernández’s best-known poetry was composed in prisons and written on toilet paper. But even the hard Izal toilet paper would have been a luxury here. Rolls of it could be found sitting on the desks of clerks who fed it through their office typewriters instead of paper.

After, his wife, Josefina, told Miguel in a letter that she and their second son, Manuel Miguel, (their first child died in infancy), had only bread and onions to eat. From that came his classic poem, ‘Nanas de la Cebolla,’ (‘Lullabies of the Onion’).

“La cebolla es escarcha

cerrada y pobre.

Escarcha de tus días

y de mis noches.

Hambre y cebolla,

hielo negro y escarcha

grande y redonda.

En la cuna del hambre

mi niño estaba.

Con sangre de cebolla

se amamantaba.

Pero tu sangre,

escarchada de azúcar,

cebolla y hambre.

Una mujer morena

resuelta en luna

se derrama hilo a hilo

sobre la cuna.

Ríete, niño,

que te traigo la luna

cuando es preciso.

Alondra de mi casa,

ríete mucho.

Es tu risa en tus ojos

la luz del mundo.

Ríete tanto

que mi alma al oírte

bata el espacio.

Tu risa me hace libre,

me pone alas.

Soledades me quita,

cárcel me arranca.

Boca que vuela,

corazón que en tus labios

relampaguea.”

(“The onion is frost

shut in and poor.

Frost of your days

and of my nights.

Hunger and onion,

black ice and frost

large and round.

My little boy

was in hunger’s cradle.

He was nursed

on onion blood.

But your blood

is frosted with sugar,

onion and hunger.

A dark woman

dissolved in moonlight

pours herself thread by thread

into the cradle.

Laugh, son,

you can swallow the moon

when you want to.

Lark of my house,

keep laughing.

The laughter in your eyes

is the light of the world.

Laugh so much

that my soul, hearing you,

will beat in space.

Your laughter frees me,

gives me wings.

It sweeps away my loneliness,

knocks down my cell.

Mouth that flies,

heart that turns

to lightning on your lips…)”

Just before his death, Miguel Hernández scrawled his last verse on the wall of the hospital next to his cot:

“Adios hermanos, camaradas, amigos,

Despedidme al sol y los trigos.”

(“Goodbye brothers, comrades, friends

Give my goodbyes to the sun and the wheatfields.”)

He died on 28 March 1942 at the age of 31 of typhus and tuberculosis in Alicante City’s prison, three years to the day after Archie and the SS Stanbrook had sailed away from Alicante.

I had an opportunity to visit Miguel’s grave and walked to it in the early sun of a hot August morning under a canopy of red Bougainvillea and through an avenue of tall Cypress trees. The cemetery was eerily quiet. As Miguel wrote: “It does not cease to be silent or to traverse it. It speaks the drowned language of the dead. Silence.” It was a deeply moving experience. He is buried with his wife and second child. Overlooking his grave, I’m sure I stood in a space drenched by many tears.

Part 3: The dark clouds of fascism return.

The poetry of Miguel Hernández lives on in so many hearts. Joan Manuel Serrat, a famous Catalonian musician who was disqualified by Franco’s regime from entering the 1968 Eurovision Song Contest because he wanted to sing in Catalan, and with a career spanning six decades, devoted an album to Miguel Hernández.

In 1974, Joan Baez sang Miguel’s “Llego con Tres Heridas,” (I Come with Three Wounds) on her Spanish and Catalan album, ‘Gracias a la Vida.’ The words are on a plinth by his grave.

“Llegó con tres heridas:

la del amor,

la de la muerte,

la de la vida.”

(“He arrived with three wounds:

that of love,

that of death,

that of life.”)

Also on his grave are his words: “Libre soy. Sienteme libre. Solo por amor.” (“I am free. Feel me free. Only for love.”)

The university in Elche is named after Miguel Hernández, and so is Alicante’s international airport.

Unsurprisingly, the stag and hen parties hardly notice Miguel Hernández’s name in big letters on the side of the airport after stumbling through customs, bleary-eyed after too many smuggled whiskey shots, boarding a coach to get legless on Benidorm Strip.

But his story doesn’t end there. In 2012 the family of Miguel Hernández expressed their unhappiness with how the right-wing Popular Party-led local authority at Elche City Hall were handling his legacy. Blaming costs, the council decided to move his archives – around 5,000 of them – to nearby Quesada, a socialist-led authority where Miguel’s wife Josefina was born.

Miguel’s family campaigned for many years to have his named cleared of ‘crimes’ imposed on him by Franco’s regime. In 2010, they got them wiped from the records. But the following year, the Supreme Court rejected the family’s petition to void the summary judgment by the Franco-era military court on the grounds that it followed the law of the time. The socialist Zapatero government’s Historical Memory Law in 2007 had allowed for pardons but did not declare pre-democratic court rulings void.

In 2024, the indictments against Miguel and several other Republicans by the Franco regime were officially annulled by the socialist government of Pedro Sánchez. The courts that condemned them at the time were also declared illegitimate. But the right-wing Partido Popular (PP) and far-right Vox – respectively the second and third largest parties in the Spanish parliament – had won control of the local council in Orihuela. With support from the PP, the far-right Vox Party opposed and blocked any annulment of the legal proceedings opened by the Franco regime against Miguel Hernández.

Laid to rest in Alicante’s city cemetery, El Cementerio Municipal, and close to the grave of Miguel Hernández are other victims from both sides of the civil war. Be they victims of air raids, like the bombing of Alicante’s food market by Italian planes on 25 May 1938 which killed up to 395 people, or those executed by Franco’s firing squads. 724 victims who were shot between 1939 and 1945, after Franco declared the war over, are also served by a memorial inscribed with their names.

After the Great War – although nothing great about it given 15 – 22 million people lost their lives – the League of Nations was set up in 1920 to prevent such a conflict ever happening again. It failed. So, after World War II, major organisations like the United Nations (UN) in 1945 and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) in 1959 were set up to ensure international peace and security. Other important bodies contributed to foster stability like the Word Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and what is now the European Union. But in a febrile world where fascism is threatening to set the world alight once again, respect for such institutions or endeavours are being undermined.

Politics is a different ball game now. The jackboots and Messerschmitts have gone. But they have been replaced with populism, culture wars, catchy slogans, lies, bribes and a contempt for international law and order.

Spain’s gross domestic product (GDP) is the best in Europe, partly because the socialist government benefits from the contribution of immigrants. But that doesn’t translate to wins in the ballot boxes. The performance of Vox – a party as close as you could get to a reincarnation of Franco’s fascists – with its strong defence of Catholicism and so-called traditional values – brags of its growing popularity. Indeed, large numbers of young people in Spain are falling for the hype with almost 40% of Spanish men aged between 18 and 34 saying they plan to vote for Vox. How long before models will be frogmarching down the catwalk in jackboots for the new Spring collection? It’s not a good look.

In 1981, Orihuela Council acquired the house where the poet, Miguel Hernández lived from the age of four. Respecting the differences of political opinions all changed in 2025 when 17 colourful vinyl plaques of the poet, erected in 2012, most of them with the Republican flag in the background, were removed from the nearby Rincón Hernandiano by Orihuela’s Cultural Department which was now run by Vox. They claimed the plaques were removed because they were “damaged”, and when removed, “further disintegrated” due to their poor condition. There were some protests in the council and police had to be called to remove protesters after the Vox Councillor for Culture, Anabel Garcia, defended their removal by equating victims of the fascists with victims of the Republicans. She said: “We must apply the same criteria of protection and recognition to the victims of the Second Republic.” Of course, there were atrocities performed on both sides, but it should be remembered that only one side overthrew a democratically elected government.

Miguel Hernández Foundation had already had its funding cut by Vox back in 2023, so it was no surprise to them to find the far-right dragging their feet when asked to return the vinyl pictures they had removed. The Partido Popular (PP) decided to abstain on the issue. Abstaining was a tactic the PP had used before when the opposition asked that the homophobic Bishop of Orihuela-Alicante, José Ignacio Munilla, who once wrote that “socialism is an enemy of the cross,” be asked to retract statements he made in support of so-called ‘conversion therapy.’ The excuse given then by the PP was that the opposition was also asking for the withdrawal of subsidies to entities linked to Munilla’s church.

Another motion that left the Vox Party without support was when they called for migrants in Orihuela all be deported to Brussels.

But there were plenty of opportunities for Vox and the PP to work together in Orihuela, for example when there was an opportunity to indulge in some standard populist fare and remove the rainbow flag from Orihuela’s City Hall. Or when they set up the Department of Family Affairs which collaborated with numerous Catholic and anti-abortion organisations, some of which, thanks to their 2025 budget, would be in receipt of grants without having to resort to such inconvenient things like ‘competitive bidding processes.’

Immigration is a contentious subject. I can understand why people are concerned when thousands of migrants pour in, speaking their own language, setting up their restaurants and businesses, occupying scarce housing, stretching resources from medical centres to schools where teachers struggle to integrate an influx of foreign children. Despite all this, Spain is not about to deport the Brits from the Costas. In any case, the British are quite capable of doing that for themselves. Riding a wave of panic over migration, the British shot themselves in the foot by voting for Brexit in 2016 which was exalted as a great panacea for the country’s immigration woes. By imposing sanctions on itself, Britain was rewarded with an estimated £140billion smaller economy, longer waiting times through customs, a block on students getting a chance to study abroad, and, with many already living abroad, British immigrants flying back to the UK if they were unable to meet their medical costs. But trusting snake oil salesmen meant that now migrants would enter the UK in even greater numbers as vacancies caused by departing Europeans had to be filled by immigrants from outside the EU. Also lost after Brexit, was the Dublin III Regulation which enabled the UK to legally return people who crossed the Channel after travelling through France or Belgium.

In the US, after the cats and dogs started eating the brains of Americans, and the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) were kicking down the doors of immigrants and picking them off the streets before deporting them, President Trump’s crackdown won the praise of the far-right mobs. But, in violation of US law, lawyers and human rights advocates were pulling their hair out over his haphazard rush to deport people without even a court hearing.

If in the US, Trump scorns democracy, it is likely because it is a law-based system that risks seeing him and his cronies thrown in jail. Like his friend Vladimir Putin whom he also sees as a ‘victim.’ There’s nothing left for the dictators but to build alliances, not with the people, but with other law-breaking autocrats that will turn a blind eye to their abuses of power.

Meanwhile, in the UK, Tories casually discuss withdrawing from the ECHR while the far-right promise to stop small boats landing on British soil despite them being no more than 2% of the amount of immigrants entering Britain.

In the UK in 2024, after the horrific murder of three girls at a dance class in Southport, the far-right spread false rumours that the perpetrator was a Muslim asylum seeker. Egged on by the lies and scapegoating of the far-right from individuals, newspapers and TV stations, mobs stormed through the streets to burn asylum seekers alive, smashing windows and setting alight former hotels that housed them. They torched mosques and attacked anyone that looked foreign or might be helping migrants who were guilty of nothing more than going through the legal process of seeking asylum. Keir Starmer’s centre-left government was left with no option but to address the ever-repeated problem of ‘small boats’ of migrants crossing the channel. Under the guise of Reform UK, the far-right were now rubbing their hands together promising that only they were the ones that would solve the problem of immigration (created by their Brexit!)

Over five right-wing Prime Ministers – six if you want to include Keir Stamer – have allowed asylum applications to build up, all the while watching the nation blame the migrants. There were fears that efficient processing would only encourage more to apply. That must have inspired Tory leadership contender Robert Jenrick to order cartoons of Mickey and Minnie Mouse to be painted over at an asylum centre for unaccompanied child migrants. Compare that to Archie’s act of kindness. What Archie showed in contrast was empathy, perhaps considering that any of those Spanish victims could have been a member of his own family escaping famine or persecution. It was not a massive leap for him to apply that same level of empathy to the gathered strangers wanting to board his boat to sail to safety. Today, the answer is in who bellows the loudest. All insisting that only they can fix migration. A cacophony of political parties is bellowing now. The loudest in Britain is Reform UK and the Tories. In Spain it is Vox and the PP.

In 2023, the PP Party took control of Alicante City council, juggling their political ideology with the needs of one of Spain’s most liberal cities. In 2025, Spain’s ruling socialist government, the PSOE named the city a ‘Lugar de Memoria Democrática.’ (A Place of Democratic Memory.) I only hope democracy doesn’t become only a memory and that this beautiful city will always be flooded with art, dance, music, poetry and colour. But if, long after his death, Miguel Hernández still felt the struggle to preserve democracy, Archie Dickson, the man who sailed those thousands of Spanish Republicans to safety, felt it even harder.

In 2024 vandals defaced Archibald Dickson’s memorial in Alicante with a black swastika.

Further Reading: –

‘The Spanish Holocaust.’ Paul Preston. Harper Press. 2012.

‘El exilio de los marinos republicanos.’ (The Exile of Republican Sailors.) Victoria Fernández Díaz. U. Valencia. 2009.

‘Captives: Concentration Camps in Franco’s Spain, 1936 – 1947.’ Javier Rodrigo. Ed. Crítica. Barcelona. 2005.

‘Los Náufragos del Stanbrook.’ (The Castaways of the Stanbrook.) Rafael Torres. Algaida Editores S A.

‘Man’s Hope’. André Malraux. 1938.

‘Adventures of a Young Man.’ John Dos Passos. 1939.

‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’. Ernest Hemingway. 1940.

‘Homage to Catalonia’. George Orwell. 1938.

‘Alicante at War: From the Republican Rearguard and Shelter City to the Destroyed, Defeated, and Francoist City.’ Rosser Limiñana. 2018. Volume I. Alicante City Council.

Documentary on the horrors of exile in North Africa. ‘Desde el Silencio,’ Exilio Republicano en el Norte de África’ (‘From the Silence,’ Republican Exile in North Africa’) by Sonia Subirats and Aida Albert. YouTube.

‘Refugees and the Spanish Civil War.’ History Today. Larry Hannant.

‘The air combat of 4 July 1938 in Alicante.’ Ernesto Martín Martínez.

‘What happened at Santa Barbara Castle.’ Juan J. Amores.

‘Repression and Exile: Landmarks of the Civil War in Alicante.’ View from La Vila. Guy Pelham.

‘From foodships to the front lines: a forgotten Manchester heroine of the Spanish Civil War.’ Angela Jackson.

‘Who are the Harkis? The Algerians who fought against independence.’ Middle East Eye. Yasmina Allouche

‘Miguel Hernández: the power of Alicante’s Civil War poet.’ View from La Vila. Guy Pelham.

‘Miguel Hernández archive: a victim of politics or economics?’ El Pais. Ezequiel Moltó.

‘Vox does not close the door to the return of Republican vinyl records from Orihuela.’ L Verdad. Jesus Nicholas.

‘Vox in Orihuela removes ‘protestable’ images of Miguel Hernandez.’ La Vox de República.

‘The hard-right Vox party is winning over Spain’s youth.’ The Economist.

‘In Spain, what once seemed impossible is now widespread: the young are turning to the far right.’ The Guardian. María Ramírez.

‘Riot at asylum seeker hotel will not stain our town’. BBC News, Yorkshire. Victoria Scheer, Tom Ingall and Phil Bodmer.

‘Trump and Putin are carrying out a pincer movement on Europe’s democracies. Suddenly, it all feels a bit 1939.’ The Guardian. Simon Tisdall.

Leave a Reply